Antoine Gléur

Antioch: the city of the finest knafeh (künefe) on the planet, with thousands of years of history on every corner. Some of the kindest people I have ever known, living side-by-side regardless of sect or origin.

I still remember the moment the earthquake happened: I was awake and browsing Facebook when one of my Facebook friends in nearby Hama posted that there was a massive earthquake. My close friend from Arsuz also called me, saying how he had to run outside holding his dog and he couldn’t contact any of his family members. In complete disbelief, I proceeded to search for more information on what happened, and even though it was less than half an hour after the earthquake, videos were already spreading of the destruction in Adana, Aleppo, and Gaziantep. I even heard from friends in Beirut and Damascus about how strongly they felt about the earthquake! The next morning, as the extent of the damage became clear, Adana, Damascus and Beirut survived in very good shape. Iskenderun, Gaziantep, Aleppo, Hama, and Maraş took some damage, but nowhere was as ruined as Antioch. The second earthquake, just hours after the first, brought down whatever survived up to that point. Living in France, I’m very fortunate to not have been affected by the earthquake personally and thank goodness none of my friends in the region were seriously injured or killed, but so many of them lost everything. My Arsuzi friend had to pay for a “free” tent from AFAD, not to mention that his fiancé couldn’t even receive money from her father in Saudi Arabia, because of how many restrictions are imposed on foreigners sending money there.

As a matter of coincidence, I was preparing to visit Antioch in April 2023, and I even booked my flight on February 3! I did not get the chance to visit before the earthquake, unfortunately, but I did visit some of the areas north of Antioch, such as Adana, Tarsus, Mersin, Iskenderun, and Belen. I also got to meet many good friends from Antioch in some of these places, and they told me about how they would be happy to host me there and show me all the tastiest foods and most important historical sites. None of which, unfortunately, came to pass. One thing that I was interested in learning about in Iskenderun and Antioch was the provenance of the French language in these places – I am a student of the French language in France, and I was wondering how much French was still used – after all, these cities were under French mandate for 17 years and some of my older friends said they either learned French in school or that their grandparents knew it well. I heard that a priest in the Greek Catholic Church of Iskenderun spoke French, so on my final visit before the earthquake, I visited, curious to see if this was true. While I did not find any priests or anyone who spoke French at the church, I did find a very nice young man, who was taking Italian lessons at the church to go study in Italy! When his lessons were done, he happily gave me a tour of Iskenderun, and we walked all along the seaside, enjoying the sunshine and fresh air. I was taking photos of everything – which I didn’t think much of at the time, but as I would later realize, those photos would serve as memories of a beautiful time forever lost…as the nice young man told me later on, “our time on the seaside is now nothing but a memory, nothing exists as it did before there.”

Eventually, I was able to make it back three times in May and June, where I saw Iskenderun, Antioch, and Süweydiye (Samandag) in various states of disrepair. First, from the Adana station, boarding the bus to Iskenderun, the driver spoke French, having lived in Paris for some time! It wasn’t just French that was being used, many people, thankfully, still knew Arabic (which I also have a slight proficiency in, as I am studying in Marseille, which is quite the Arabic-speaking city itself!). Waiting next to me for the bus was a young man, a student from Iskenderun in Izmir, and he still knew fluent Arabic, which was quite a pleasant surprise considering: not only are the younger generations losing Arabic, not only is this especially present in Iskenderun, but also that he was studying in Izmir, where Arabic isn’t used. I sat next to a very nice older man from Harbiye, who told me how much he liked Najwa Karam’s music and showed me some of his favorite clips of it! In general, I also heard people talking on the phone to their relatives in Arabic, which made me happy that, despite displacement and everything that had happened, they were determined to hold on to their heritage.

When we arrived in Iskenderun, the damage was quite a shock. Many buildings just collapsed among others which were entirely intact, so it was quite haunting to think that within meters of each other, someone living in one building could have been spared and someone else didn’t make it. Not to mention all the buildings which were partially collapsed, and still standing on their last legs. At least there was still life in Iskenderun, though, as people were walking around enjoying ice cream and coffee on the seaside. There were enormous cracks in the corniche, though, many stones were missing, and parts of it were flooded. When I visited some stores, and later, the bus station, the immense internal damage to buildings was quite evident. There were cracks all over the walls, and in particular, the bus station seemed to be at risk of collapse. City parks and empty spaces were full of tents, to look after those who lost their homes. Despite this, however, people said that since they had nowhere else to go, they would continue as best as they could, because what else could they do? As bad as conditions in Iskenderun might have been, it’s their home at the end of the day, and leaving your home, for any reason, is the hardest thing of all. This was nothing compared to the horror of Antioch, though, as I would find out the next day.

Ascending by bus up the Nur Mountains as it left Iskenderun, the highway to Antioch was spotted with tents and ruins of buildings. As the bus got closer to Antioch, many industrial ruins were piled at the entrance to the city, creating a very large dust cloud. Crossing the bridge over the Orontes, not a single building in sight remained intact. Rubble and garbage were piled on the streets, and the river was a murky dark brown, with a very strong smell. Exiting the bus station and making my way to the riverside promenade of Antioch, I could hardly believe how much of the city was just empty lots. So much was damaged beyond the point of repair that whole neighborhoods were left flat, cleared out by bulldozers, erasing the final memories of daily life there. Most of all, though, I could hardly believe that three months before this was a bustling, safe, prosperous, cultural, hub with some of the kindest, most hospitable people I had ever met. And now, one of the worst catastrophes imaginable had just befallen them through no fault of their own. At the central roundabout, near the entrance of the old city, there were several makeshift shops with kebabs and such being sold, and next to them, standing by the river, was an old lady singing in Arabic after she lost everything in the earthquake. It was beyond words – among the ruins, in her worn and dirty clothes and having nothing left, she was still trying to carry on in the hope of a better tomorrow. The old city itself was in no better condition. Among the shattered and damaged shops lay all manner of historical buildings in ruins. The churches, mosques, synagogues, hotels, and restaurants were all more or less reduced to rubble. Not a single building was inhabitable for almost as far as the eye could see, particularly around Kurtulus Street, the former bustling core of Antioch. Many cats were roaming the rubble, as well as flies, buzzing around dead bodies lying underneath. And yet, on the outskirts of Antioch there were still a few who remained in their homes, washing their clothes on corners and selling flowers on the side of the road. Sitting at tables and catching up. Life really does go on, and it never entirely stopped in Antioch.

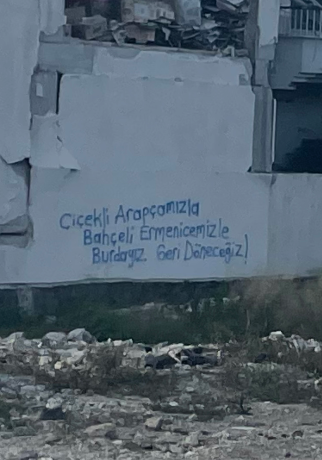

Returning later for a visit to a friend in Süweydiye, I boarded the Antioch-Süweydiye bus line and could see the entire panorama of Antioch: the green mountains overlooking the Orontes River and the ruined city below. The bus passed several shops and houses with Alawi swords displayed on them, owing to the town being predominantly Alawi, as well as many bearing the original Arabic name – noted here as Süweydiye. The bus also crossed a bridge dedicated to Ali Ismail Korkmaz, a young man martyred in the Gezi Park protests in 2013, who came from the town. Tetas sat on the side of the road and chatted among the ruins, and graffiti on a nearby building read “Çiçekli Arapçamızla / Bahçeli Ermenicemizle / Burdayız. Geri Döneceğiz.” The bus let me off right next to the beach and the iconic Hazreti Hızır tomb, where I met my friend. We had a very joyful reunion, despite everything, it was so nice to see him. As the sun set, we sat on the beach. I spoke to him in my limited Arabic, and whatever we couldn’t express, we resorted to drawing in the sand to convey. I still remember how, even though he had lost everything, he said that his tent was my tent, and I could sleep over with him. This kind of kindness and openness has really impressed me with the people of Antioch, even before the earthquake. I was never treated as kindly as this anywhere else I went in the world, and this is not from only one experience, my multiple encounters with the beautiful people of Iskenderun and Antioch have demonstrated this time and time again.

So, as we consider the aftermath of the earthquake, we mourn for the dead who perished under the rubble of woefully inadequate buildings. We mourn for the living, who are condemned to a life under tents and surrounded by rubble, which is even causing cancer. But most of all, we mourn for the city lost, and hope that it can one day be rebuilt to its former beauty.

“Ma rihna nehna hon!”